A Few Newer Stories

The Education of a Trumpsogynist

This old story of mine stuck in the mind of Baynard Woods, a reporter on the Baltimore City Paper. He wrote a country-music song about it. I’d like to think that “News to Me” is my turn to be a journalistic banderillero, flicking a protective cape for a new generation of reporter-matadors.

You can dance to it. (When you’re done, read the story.)

Banderillero

“Just because your legs is dead don’t mean your head is.”

–Casey Stengel, New York Yankees

Villamuellas, Spain

Soldiers don’t start out as generals nor politicians as presidents. In business, managers work their way up. Except for a lucky few, the realization slowly and steadily comes to just about everyone that the top is out of reach.

But bullfighting works the other way around. A bullfighter rockets to the top. From first blush, he is a matador—that bold and arrogant swordsman who artfully entices the bull to its moment of truth. A matador monopolizes the spotlight long enough to convince the world of his incompetence. Then his own moment of truth arrives: the shock of failure and the dawning knowledge that he will never be on top again.

The truth came to Ernesto Sobrino thirteen years ago.

“People stopped taking me seriously,” he says, driving his own car through a rainstorm, heading out of Madrid and across the Castilian tableland to a bullfight in this little town. He is forty. His chestnut hair is all there, but he appears to have a small pillow under his worn blue sweater.

“Life as a matador became a life of pain,” he says. “People made fun of me. Promises were never kept. When I was twenty-seven, I faced reality.”

A bull gets dragged to the butcher’s after its moment of truth. A matador, if he stays alive and retains some spunk, gets to be a banderillero. That’s what Ernesto Sobrino is. So is his friend, Paco Dominguez, who is riding in the back seat. His hair is going, but he wears his jacket draped over his shoulders and carries his cigarette with his arm raised, as if acknowledging an ovation.

“The bullfight is a liberation,” he says, blowing smoke into the front seat as the car circles the great stone bullring in Aranjuez. “We risk our lives with joy.”

Sobrino pulls out a rag and wipes the condensation from the inside of the windshield. “Paco,” he says, “you’re a romantic. For me, everything is practical. Gambling with life and death is the way I make money. When you are a matador, you can dream. When you are a banderillero, you have to stop.”

Banderilleros are the old men of the bullring. Suited up, these bullfighters look like thick-waisted versions of young matadors. The crowd has a chance to take special note of them when they run at the bull with two barbed sticks and try to place them in its hump before the matador moves in for the kill. A hardy banderillero can keep at this until he is past fifty, although his run will inevitably seem longer every year.

Apart from those two seconds when he places the sticks, the old man’s job is to make the matador look good. While the matador struts in front of the bull, taunting it, daring it to charge, the banderillero hovers in the background, an experienced eye on the animal’s every twitch. When the matador fumbles, a flick of the banderillero’s cape can, by distracting the bull, save the matador from a horn through the thigh and, occasionally, from humiliation. All the old man craves in return is some respect and a day’s pay.

Villamuelas appears at the base of a slope: half a dozen streets of two-storied buildings. The bullring is just outside town. It is portable, made of corrugated tin and set up in a muddy field. Spain has fewer bullfights than it did before television and the family car. A banderillero takes what he can get.

“It’s your legs and your head,” Ernesto Sobrino says as he parks his car in front of the bar in the village square. “You need both. I jog. I don’t drink or smoke. The crowd doesn’t cheer for me. I’m beyond the point where I expect to be a star. But we are the pillars of the bullfight.”

The rain has eased off. A woman is washing out of few things at the fountain. A man is selling fried dough. Strung between two balconies, a banner announces today’s fiesta. The bar is packed, its floor littered with shrimp shells. The band sprawls on plastic chairs, drinking coffee. Men in berets lean on canes, wine glasses in hand. Sobrino works his way through, orders an anisette, then remembers he doesn’t drink.

“Just a little,” he says. “It warms my stomach. I haven’t smoked for a week now.” Paco Dominguez lights up. “Must you?” Sobrino says. But Dominguez ignores him—the matador is coming in: tall and svelte, chin held high, hair jet black, eyes hidden behind dark glasses. He is a novice, perhaps twenty-years old and, Sobrino confides, without promise.

“A rich kid,” he says.

“He comes from a wealthy family,” says Dominguez, turning back toward the bar. “His family is investing in him.”

“I never had an investor in my life,” Ernest Sobrino says.

His story is the standard one for bullfighters. He was born in a town like this, left school at eleven, delivered groceries, studied bullfight newspapers, worshipped Manolete. He walked all night to small-town capeas—illegal fights in rings built of boards and parked cars. At fourteen, he stood in front of a bull. At sixteen, he was gored. At eighteen, he was noticed. He dressed as a matador for the first time a year later, in 1961, and killed his first bull.

“I always thought I was good,” he says, sitting down under the bar’s television, which is showing a bicycle race. “There was one day in Rioja. I had a good bull that day. I mastered it. I was artistic. I cut two ears. For me, this was success. But I don’t build sand castles; life proved me wrong.”

He sips his anisette, and looks up at the bicycles.

In the bullfight business, the impresario pays the matador, sometimes well. The matador pays his banderilleros, though not always on time and rarely well. As Ernest Hemingway wrote years ago: “There is no man meaner about money with his inferiors than your matador.” The banderilleros suffered on. Not until the start of this season did they finally vent their resentment. They walked out.

Their strike lasted a week in March. When it was over, they had won a pay raise of fourteen percent. Now a banderillero gets at least $400 for fighting in a first-class ring. In Villamuelas today, Sobrino should come away with $150. Crisscrossing Spain all summer, he might hit fifty towns and earn $10,000. The extra money will help. But when a bullfight is called off, a banderillero still gets no pay. Nor does he have much of a future once those legs go.

“Money isn’t all that important to me,” Sobrino says as he drains his anisette. “I’m sincere about that. I’m talking about dignity.”

Lunch is ready. The bullfighters and their entourage file past the bar into a bare hall at the rear. A movie screen hangs from the far wall, a stack of chairs in front of it. Two long tables have been set up in the middle of the hall. The matador and his family sit at one. The banderilleros and the picadors, who fight on horseback, sit at the other. So do a few of the impresario’s functionaries, one of whom goes by the name of Cadeñas.

Cadeñas is getting old. He has a throaty voice and puffy skin. When Ernesto Sobrino was a matador, Cadeñas was already a banderillero.

“For thirty-five years I was a bullfighter,” he says, spitting out and olive pit. “Now I sell the tickets.”

“When I’m through,” Sobrino says, “I’d like to be a TV repairman.” He takes a sip of wine and looks down at his plate. “The pork is tough,” he says.

By late afternoon, when lunch is over, the crowd fills the square. The band plays the Pasodoble Torero. The loudspeaker crackles: “The greatest spectacle of bullfighting this afternoon in this wonderful city! Get your tickets now! A sensation!” The bullfighters begin to dress in the bedrooms on the other side of the bar. Then the rain comes down.

The impresario returns from the ring, his shoes muddied. “Impossible,” he says. The mayor of Villamuelas steps out onto the balcony of the town hall, overlooking the square, and addresses the townspeople. The spectacular, he announces, is canceled.

Sobrino folds his cape. “A funeral,” he says. “We don’t get a peseta.” He and Paco Dominguez drive back to Madrid to wait for the sun, stopping on the way for another anisette.

Two days later, the sun shines on the fiesta of another Castilian town, San Martin de la Vega. The bullring has been erected right in the square, and the cobbles covered with sand. This ring is dangerous. It has too few places for a bullfighter to hide. Looking less than lithe in his salmon-pink suit, Sobrino is keyed up, his face in a fixed grin.

“Sometimes I suffer so much fear in the ring I don’t even see the women,” he says, surveying the crowd from behind one of the barriers. As a banderillero, he has twice been seriously gored, both times in the groin. “Every time I get dressed for the fight,” he says, “I know it can happen again.” He takes a swig from a wineskin and shows his teeth to the fans.

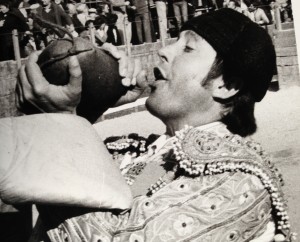

The preliminaries soon end and the fight begins. As each bull charges into the ring, Sobrino hangs behind the barrier, letting the matador who employs him today show off his capework. On his first run, the banderillero plants the sticks perfectly, without the slightest attempt at pizzazz. On his second, the sticks go flying. The bull wheels and gives chase. Sobrino flees, stiff-legged, over the barrier, with a look on his face of crazed concentration.

It is the only moment all afternoon when the crowd pays him any heed. After his young matador gracefully dispatches the day’s final bull, the coup de grâce is left to Sobrino. He performs it with a sharp jab of a short knife, and cuts two ears for the youngster, just as two ears were cut for him on that day in Rioja. Flowers shower down. Sobrino stoops to collect them and presents a bouquet to another novice in his glory.

The bullfighters parade in triumph and disappear beneath the stands. As the crowd leaves, someone lets a spindly horned calf run loose in the ring. The boys of San Martin de la Vega jump down onto the sand to dance circles around it, acting out their fantasies of becoming matadors someday.